Cheryl Hudson Shares Stories at MLK Charter School in New Orleans

10 Dec Continuing Our Author Visit to Martin Luther King, Jr. Charter School, New Orleans, LA

Continuing Our Author Visit to Martin Luther King, Jr. Charter School, New Orleans, LA

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

In association with PEN Children’s & Young Adult Book Committee

CHERYL’S STORY

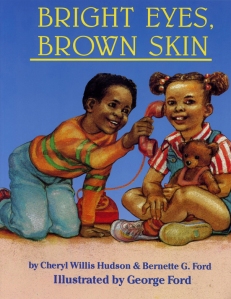

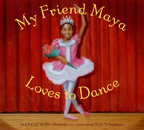

I entered Ms. Bryant’s first grade class at 9:30 am armed with my computer notebook, and a big red bag filled with props, books, and paper handouts. My idea was to set up the computer with my PowerPoint presentation, read from either Bright Eyes, Brown Skin or My Friend Maya Loves to Dance, answer a few questions about how a book is actually made, and then explain in 10 minutes or less how my job was actually 3 jobs in one: an author who write stories, a creative director who puts authors’ words and artists’ illustrations together to make picture books and a business partner with my husband to market and sell books and get them to readers.

Clothes I Love to Wear by Cheryl Willis Hudson, illustrated by Lauara Freeman, published by Marimba Books.

It was an ambitious plan to cram into 50 minutes and 18 anxious faces were eager for me to start. After Mrs. Bryant and the IT manager hooked up my notebook to the big screen projector, I realized that it was keyed to the wrong PowerPoint presentation. Jazz music was playing as background to a trailer for another title, Clothes I Love to Wear and the children were responding in unison, “Ooooh!”

So what did I do? I chucked my original plans, improvised and asked questions: “How many of you use your imagination?” “How many of you like to play dress up or make pretend?” I began reading Clothes I Love to Wear instead of the title I had originally planned.

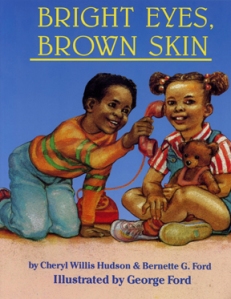

The students were so enthusiastic, I barely had a chance to get the props out of my bag. (derby top hats, magic wands, tutus, masks butterfly wings, and kente cloth that I planned to use for My Friend Maya loves to Dance.) Then the students volunteered to help me hold the big book version of Bright Eyes, Brown Skin. They joined in the call and response:

Bright eyes, brown skin

A heart-shaped face, a dimpled chin.

They demonstrated along with me skin, eyes, ears, fingers, nose, toes, and very special hair and clothes. I was energized and impressed by the students because they had read several of my books before I came. They and their kindergarten schoolmates had even prepared individual drawings to illustrate that book.

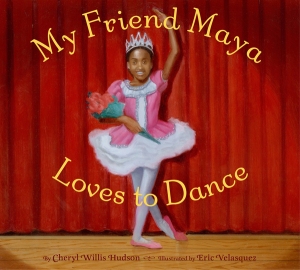

When it came time to read My Friend Maya Loves to Dance, I asked for volunteers to dance with me. One young man shouted out, “I didn’t know that dudes could take ballet!”

“Of course they can and they do,” I replied, showing them the detailed and realistic paintings done by Eric Velasquez. Before I could say, “Laissez les bons temps rouler,” I was surrounded by boys and girls demonstrating dance positions with me. Boy was that fun!

My Friend Maya Loves to Dance by Cheryl Willis Hudson, illustrated by Eric Velasquez, Abrams Books for Young Readers.

Briefly, I explained the differences between concept books, board books, paperback picture books and hardcover titles using title such as AFRO-BETS ABC Book, Good Morning, Baby, and Construction Zone to demonstrate.

When the students saw the photograph of the big caterpillar on the cover of Construction Zone they immediately related it to construction equipment in the Ninth ward and all over New Orleans where buildings were being razed, rehabilitated and constructed from new foundations.

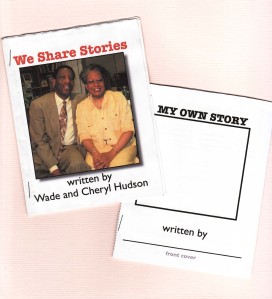

After talking about my writing process as an author, I told the children that my other job was to help other people tell their stories by publishing them as books through our publishing company, JUST US BOOKS. That concept was a little bit harder for them to grasp, but showing them a little mini-biography of Wade and myself and our company helped to make it our role a little clearer. Using an 8 ½ x 11 sheet of paper folded twice, I demonstrated the covers, copyright page, title page and formats for interior pages of a book.

The hour flew by so quickly, but there was still time for everyone to stand and one-by-one share the title of a story or a book that they had recently read. It was clear that these students loved to read!

Mrs. Bryant’s entire class could have been poster kids of Bright Eyes, Brown Skin. I was inspired by their warmth, curiosity, enthusiasm and genuine joy for reading books. I can hardly wait for them to share their creative writing assignment with us in the future.

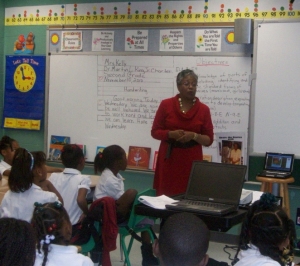

For my presentation for the 2nd grade, two classes of about 40 students filled the space in another classroom down the hall from Ms. Bryant’s. The 2nd graders had read Glo Goes Shopping. And they were familiar with My Friend Maya Loves to Dance as well. For this group I went into a bit more detail about the value of brainstorming an idea and the importance of telling your own story. (Who indeed could tell it better? Who could best tell it from your point of view?)

We talked about the building blocks of stories; how alphabet letters are basic; letters form words; words form sentences; sentences form paragraphs and together they become the vehicles for writing and telling a story that may eventually become a book.

Every story begins with a seed of an idea and the 2nd grade students had plenty of them! They knew stories could be about family, friends, neighbors, pets, field trips, or something entirely imaginary!

For example, the students liked Glo’s story because she went shopping (something they all liked to do) for a friend, but during the process she found out a few interesting things about herself and learned about the value of sharing and of friendship. The students agreed that the best gift that Glo could give was something that she could really share with her friend, Nandi.

When I asked the children if they used their imaginations to think about their individual gifts and what they wanted to become when they grew up, a young lady sitting directly in front of me replied without hesitation, “I want to be the president of the United States!”

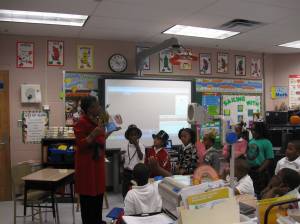

Other children wanted to be a princess, an African chief, an entertainer, a doctor, a lawyer, a king, a tap dancer, a writer, an illustrator and a mayor. Together, they enthusiastically acted out each scene for their fellow classmates as I read My Friend Maya Loves to Dance.

Students demonstrate a line from the text of My Friend Maya Loves to Dance. "She holds her arms high to reach for the sky."

Toward the end of our session, one young man, Julian, volunteered to share a story he had written about a big pumpkin. He retold a story they had studied in class but gave it with a different ending and rewrote it using new vocabulary words. We agreed that one day he might become a published author. If he took his story, re-wrote it and put it into the template, made copies of it and distributed it to a larger audience his work would be “published” or made available to the public. It could be a printed book or even an e-book if it were published online!

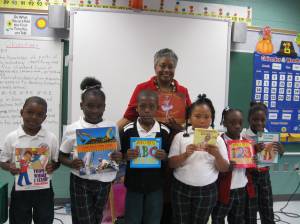

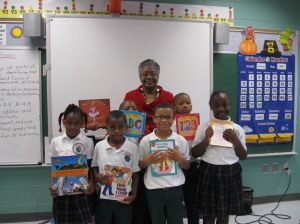

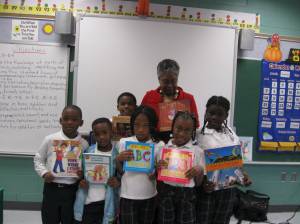

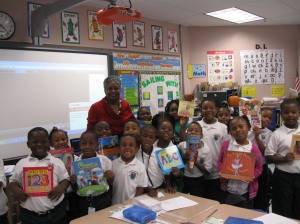

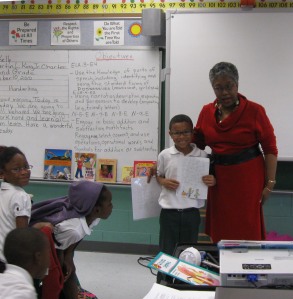

I ended the session by handing out templates the students could use to create their own mini-books, awarding certificates of participation and taking photographs of Ms. Kelly, Ms. Ford and all of the students. I’m not certain that I made all of the points I had planned for this presentation, but I certainly learned a lot by sharing with all of the Martin Luther King Charter School students. I’m anxious to come back to New Orleans so we can share even more stories that the children have created themselves.

Next Blog: Photos of 1st and 2nd grade students at author visit, MLK Charter School, New Orleans, LA

Sharing Our Stories at MLK Charter School in New Orleans

9 DecOur Author Visit to Martin Luther King, Jr. Charter School

New Orleans, LA

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

In association with PEN Children’s & Young Adult Book Committee

We began preparing for our visit to Martin Luther King Jr. Charter School months before actually reaching New Orleans. We knew that we’d be doing double duty as both authors and as publishers and we were pretty much prepared for that. But there was added excitement surrounding this particular visit because in a sense, Wade would be returning home.

A native of Louisiana, Wade had attended Southern University in Baton Rouge during the 1960s and was familiar with the area and the culture of New Orleans. Other PEN members had visited MLK in the past two years, but Wade would be the first black male author to visit MLK and would perhaps relate to the students in a more personal way because of their common backgrounds.

Although we had visited Louisiana a number of times for teacher and library conventions and to visit family, we had not returned to New Orleans since the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina.

Would we recognize the city? Would we feel comfortable staying in tourist digs near the French Quarter and then traveling to the still devastated Ninth ward the next morning to visit the only school in that entire area of the city that was open and functioning? How would the staff and students receive us?

Any doubts or fears dissolved when we were greeted and received literally with open arms by the staff and by the students. We went to New Orleans as representatives of Just Us Books—prepared to “Share Our Story” but we both came back energized, renewed in spirit and with many more stories to share.

WADE’S STORY

I was born and raised in Louisiana and attended Southern University in Baton Rouge. So I was anxious to visit my home state, and the city of New Orleans and speak to students at the Martin Luther King Charter School. Although I had visited New Orleans several times since I moved from Louisiana, I had not been there since Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005.

Mrs. Karen Ott, a member of the MLK School staff, picked up my wife Cheryl and me from our hotel to take us to the school. On the drive to Caffin Avenue, she showed us some of the areas of the city that

had been damaged by Hurricane Katrina. Some of these areas had rebounded in a strong way from the devastation and destruction. That was especially true of the French Quarter.

But in many other areas, it seemed that much still needed to be done, especially in the Lower Ninth Ward where the MLK Charter School is located. Yes, there was some home construction taking place, but it appeared to me that the

Some new housing in the Lower Ninth Ward, sponsored by actor Brad Pitt and his not for profit organization.

Lower Ninth Ward was quite a ways away from being a bustling, viable community—alive and vibrant. My spirit was a little low as we continued to ride around the area and saw so many boarded-up churches, schools and other buildings.

This post by Tracie Gallagher, which appeared on Fox News.Com on August 23, 2010, really says it all.

“Five years after Katrina many parts of the lower 9th ward look like the flood waters just receded yesterday.

Many of the damaged and destroyed homes have not been touched at all, in fact many still have those infamous red Xs painted on the front, indicating the date the homes were inspected and how many bodies were found inside.

Clearly the recovery and rebuilding process is moving at a snail’s pace.

Before Katrina there were 5300 homes in the lower 9th ward. Every single one of them was flooded and uninhabitable. Now only 1200 have been repaired or rebuilt.

The main reasons more people haven’t come back to the 9th ward is because there are only three volunteer organizations building homes, and they don’t have enough money or resources to build faster.

And the infrastructure in the lower 9th is still almost nonexistent. No fire department, no hospitals, no grocery stores, and only one elementary school, the other students are bussed miles away.

But the people who have returned are proud and passionate. And when the 9th ward rises again, (and it will indeed rise) it will be those who came back first who inspired those who came back eventually.

When we arrived at the MLK School, however, I perked up. As I looked at the structure, it stood as a beacon of hope for the Lower Ninth Ward, a clear example of how the communities of the Ninth Ward and New Orleans can come back even stronger.

Mrs. Ott escorted Cheryl and me into the building where we were treated to coffee and doughnuts and were serenaded by a recording of the school’s song. Soon Mrs. Doris Hicks, the school’s dynamic principal, came to greet us. We were already aware of the tremendous role she has played in bringing MLK School back following the hurricane and flood, and how she has overcome so many obstacles and challenges in her mission to make MLK a stellar academic institution.

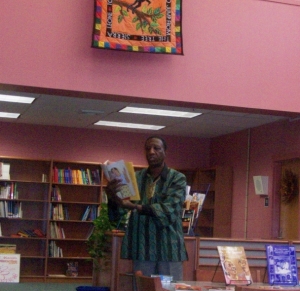

After our chat with Ms. Hicks, Mrs. Ott escorted Cheryl to a first grade classroom, and then led me to the school library where I was to make my presentations to two fifth grade classes. The library serves a dual role. It is a part of the New Orleans Public Library System and is open to the community, and it is used by the MLK School.

My first group of fifth graders had read Anthony’s Big Surprise, the third book in the NEATE series I created for Just Us Books. The second group had read Book of Black Heroes: Scientists, Healers and Inventors, a title in the Book of Black Heroes series I developed for Just Us Books.

As the students assembled in the large library reading room one asked a question I could not quite hear. I was told that he wanted to know “where my wife was.” I was also told that the student was relating us to President Barack Obama and his wife, first lady Michele Obama. The President had paid a visit to MLK during the 2009 school year. The question made me realize further how important role models are. Because of our visibility as writers and publishers, many people see my wife Cheryl and me as role models. Over the years, we have readily accepted and embraced this position. But being mentioned in the same sentence as the first African-American President, his intelligent, beautiful and charming wife and family brought a smile. I understood the association, but the responsibilities and challenges Cheryl and I face are quite minor compared to those faced by the first family.

The students sat attentively as I shared with them my story. I was born in a small town nestled in the northwestern section of the state, south of Shreveport. Mansfield was and still is a small rural town. I grew up during a time when most cities and towns in Louisiana and in the South were segregated and Jim Crow Laws still governed life for blacks and whites. (Ironically, even today, many communities and schools in New Orleans and around the state of Louisiana are still segregated.) The Civil Rights struggle had begun to make a big difference, but major changes still needed to be achieved in the fight for racial equality and justice.

I shared how our all-black schools received books that had been previously used and discarded by the students at white schools in my hometown. These books had virtually nothing in them about African-American history, culture and experiences. Our school library was void of books that included stories about black people or books written by black writers. So for me, and many of my peers, great writers such as Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston and Gwendolyn Brooks didn’t exist. As a youngster growing up, I told them, I enjoyed writing and often wrote poems and short stories. I never considered writing as a career. I knew it was a gift that I had been given, but, at that time, I didn’t see writing as a vehicle for me to make my contributions to the world.

Wouldn’t it have been wonderful if I had had the opportunity to read the works of great black writers such as Hughes, Ellison and Hurston? They would have been ideal role models for a little black boy discovering the gift with which he had been blessed. It wasn’t until I entered Southern University in Baton Rouge that I learned about black writers who had made significant contributions to the worlds of literature and history. It was then, that I realized I too could have a career as a writer.

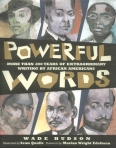

I told the students that I have written nearly 30 books for children and young adults. That I also penned plays that have been produced professionally, worked as a newspaper reporter and in public relations where I have used my writing skills. Many of the books I have authored were on display in the library for the students to see. Then I shared how, in 1988, my wife Cheryl and I started our own children’s book publishing company, Just Us Books, Inc. to produce children’s and young adult books that spotlight, highlight, explore black culture, black history and black life experiences.

I told the students how important it is that they learn about the history and culture of their ancestors. That it is important that their experiences be shared to help educate as well as entertain others and make others aware that we have a world shared by many different races, ethnic and religious groups. That it is crucial for any child or young adult to see characters that look like him or her in books, on television and in movies and in all others modes of communication.

Near the end of my presentation to the first group of students, I read from Anthony’s Big Surprise from the NEATE series. The series features five African-American eighth grade students who live in the same community and attend the same junior high school. Determined to support and encourage each other, they use the first letter of each of their first names to name their group – N for Naimah, E for Elizabeth, A for Anthony, T for Tayesha and E for Eddie. Anthony’s Big Surprise focuses on 13-yeaar-old Anthony, who is being raised by a single mother. Anthony’s mother has told him that his father was killed when Anthony was very young. When the story opens, Anthony is receiving expensive anonymous gifts. He eventually finds out that the gifts are from his father, who, in fact, is not dead. I read from the scene where Anthony finds out that his father isn’t dead, the heart-wrenching and challenging moment where he first meets his father in the principal’s office.

“Anthony was getting confused. The name was right. The instrument was right. Could this man really be his father? If so, that would mean his father wasn’t dead. But wait, a family friend could know that much. In fact, anybody could know as much as this stranger knew. But why would anyone who wasn’t Anthony’s father want to go through all this?”

Following the reading I engaged the students in a lively discussion. I asked questions such as, “If you were Anthony what would you do?” “Would you accept a father who has never been a part of your life?” Most of the students had strong opinions. Many of them were being raised by single mothers and could relate to Anthony’s situation. Most of the students said they wouldn’t accept a father who has not been there for them. The father, they felt, should earn an acceptance.

MLK 5th graders listen to author Wade Hudson's presentation in the library.

For my second presentation of the day, I read from Book of Black Heroes: Scientists, Healers and Inventors. The book was written to introduce young readers to some of the many African Americans who have made important contributions to science, medicine and invention. I thought this would be particularly appropriate given the MLK Charter School’s focus on science and technology.

I really enjoyed my visit to the MLK Charter School. The students were well-mannered, inquisitive and bright. They asked provocative and well conceived questions. A generation ago, I was in their shoes, eager and anxious to learn as much as I could, looking forward to a brighter future beyond situations that would paint a bleak picture of what lay ahead for me. I felt a real connection to these students. As I signed copies of my books each of them held, I had an opportunity to chat with some of them and to look into their faces and share smiles with them. As I left the library following my last presentation, I felt assured, in the hands of these students, the city of New Orleans would be just fine.

Next blog: CHERYL’S STORY

For the Joy of Dance and Books about It

19 OctLast week I happened to see a review of one of my books on Goodreads that caused me to pause. The review was not particularly flattering and I thought the reviewer entirely missed the point of the book. I decided (for the first time in my career as an author) to respond to it online. Following is the review and my response.

Library Lady http://www.goodreads.com/user/show/288297-the-library-lady wrote:

Why can’t an African American girl who loves ballet just dance ballet, and ballet alone?

Why does she have to dress up in kente and cowries to offset her ballet class? Would an Asian child have to wear a kimono or a Jewish child have to be shown dancing the hora?

This is a beautiful ballet book. The lines of the illustration are pitch perfect. The correct ballet terms are used. And if you insist on being politically correct, Maya’s teacher is also African American, a grownup black ballerina!

But adding the other dance bits seems to say, “It’s okay. Maya is an African American girl who likes ballet, but she’s still a homegirl.”

It’s gratuitous. It’s unneeded. And it does injustice to girls who love ballet, no matter what the color of their skin.

This is my response.

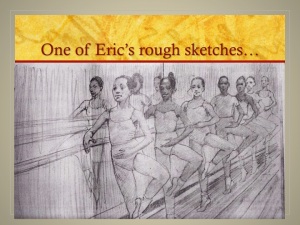

As the author of My Friend Maya Loves to Dance my perspective is quite different from that of the reviewer. I wrote and Eric Velasquez illustrated a story called My Friend Maya Loves to Dance. What Library Lady has done in a few short sentences is to misconstrue the title and content (the title is not My Friend Maya Loves Ballet). In so doing I believe she has shifted the focus of the review from coverage relating to the authenticity of the real story to a commentary that expresses her own views on political correctness and how diversity should or should not be depicted in this particular title or perhaps in books in general.

Maya loves to dance. Period. Since music is her muse and she loves all kinds of music, Maya loves all kinds of dance. Ballet and western music are part of her repertoire but they are not the basis of it. Maya loves jazz, blues, rock, reggae, and gospel. She loves praise dancing, tap and ballet. Those facts are clearly stated in the text. Incidentally, through the art, it is apparent that all of these forms/styles of dance are being offered in the dance studio where Maya takes lessons and/or she engages in them outside her lessons. Clearly, Maya loves to dance!

Maya is a homegirl. But that is positive terminology for her, not the negative jargon the reviewer’s words seem to suggest. Dance is core to Maya’s being and she expresses joy in her African American heritage naturally and innately, not in opposition to or as an offset to another standard. The fact that she studies ballet is simply that. Maya takes ballet lessons. She dances because it brings her joy.

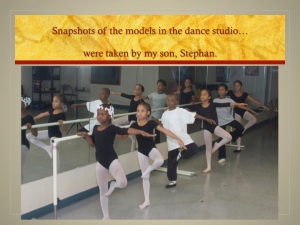

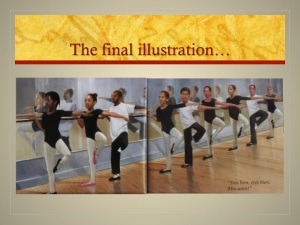

I am somewhat reassured by Library Lady’s words: “This is a beautiful (ballet) book. The lines of the illustration are pitch perfect.” (The words are hers but the parentheses are mine and I’d suggest deleting the words “ballet” from the first sentence). “The correct ballet terms are used.” The Library Lady must love ballet herself. But for her to suggest that the other “dance bits” are gratuitous and unneeded does an injustice to the storyline as well as to the author and the illustrator. I too love ballet but I did not write a book solely about ballet. The models for this book are real people who live and work in my community which is similar to communities elsewhere in this country. The basis of the story is my experience as a black child taking dance lessons over 50 years ago as well as witnessing the young dancers in a local dance (not just ballet) studio.

And yes, Maya’s teacher is African American–a grownup black ballerina! Her presence in the story has nothing to do with political correctness. She is based on an actual person, and like many women and men around the country teaching dance is what she does for a living.

Authors and illustrators spend a great deal of time, thought, research, imagination and creativity in their collaborative efforts making good picture books for children. Of course, all reviews show some degree of subjectivity and that is to be expected. However, I think Library Lady has missed an opportunity for fairness and objectivity. Her review seeks to make a dance form and those people that perform it exclusive, rather than inclusive. Maya loves to dance, and I invite those of us who also exalt in this diverse form of expression to embrace Maya and her diversity.

What say you?

Threads: A is for Anansi in Literature for Children

11 OctThere were some incredible presentations, discussions and conversations at the A is for Anansi Conference: Literature for Children of African Descent held at NYU this past weekend. (October 8-9). I’d like to share a few threads beginning with the notes I prepared for a panel that I moderated concerning the History/Significance of African American Literature for Children. Panelists included Kathleen T. Horning, Joe Monti, Colin Bootman, Regina Brooks and Hannah Erlich.

Mega thanks go to organizers Jaira Placide and Rashida Ismaili and for the sponsor of this historic conference, NYU’s Institute of African American Affairs under the direction of Manthia Diawara. Thanks for inviting me, Wade and Just Us Books to participate and to share our perspectives at the conference.

Time constraints prevented me from posing all of the questions I would like to have asked the panelists, but I am posting them here as a reminder of both the framework for the discussion and other ideas not covered over the course of the conference that I’d like to discuss in this blog. As days progress, I hope to post additional threads in this complex web of thoughts and ideas and action points surrounding issues in African American literature for children.

“Until lions have their historians, tales of the hunt shall always glorify the hunter.” –African Proverb

Scholar and children’s literature expert, Rudine Sims Bishop writes the following words in introductory comments of her book, FREE WITHIN OURSELVES: “The seeds of an African American children’s literature were sown in the soil of Black people’s struggles for liberation, literacy and survival. For those seeds to develop into a body of written literature or children, there first had to be, among other things, a critical mass of child readers, a collective recognition of children as a reading audience distinct from adults, and a significant number of writers willing to address their work to that child readership.”

As the panelists prepare to make their presentations, I would like to propose these questions for all of us to consider.

1. How relevant is an historical perspective in terms of creating, developing, marketing and selling books for and about children of African American descent?

2. Contemporary children in the US today are more than 55 years removed from the historic 1954 Supreme Court Decision that stuck down “separate and unequal schools” for its citizenry. How realistic is it for them to be curious about that decision’s ramifications in literature in 2010? Does it matter?

3. Should children’s books be “color-blind”? What do you think that term means to parents who select and buy books for their children?

4. Let’s talk about authenticity, content, canon, and critical mass. Who should be telling, editing, marketing and selling African American stories?

6. Some writers have suggested that multicultural literature should be mirrors and reflectors for diversity in our nation. What are some practical ways to share books cross-culturally?

7. President Barack Obama was shown earlier in the year reading a picture book to a group of children at a White House gathering. What African American title (or book written and/or illustrated by a person of African descent) would you suggest that he read at the next setting? What books would you suggest for Sasha and Malia?

Publishing in Color

7 JulWhite and Whatever…

Harlem Book Fair: Why, in 2010, when the nation has elected its first African American president, is the book publishing industry still not meeting the need and demand for books that explore the width and breadth of our country’s multicultural experiences?

A panel of professionals will explore the complex issues and suggest solutions to a problem that is garnering a lot of attention. Please tune in on July 17, 2010 via C-SPan Book-TV for this discussion.

Following Independence Day I issued a Facebook challenge to my friends to provide a list of 20 African American editors of Children’s and YA books. A day later no one had submitted a complete list of folks currently working in the industry. At most, an informal committee came up with a list of 30 POC. There were lots of comments about the whole challenge and below is a list of a series of responses I had to my friends via FB and personal e-mails.

Some of the questions included: How many POC apply for jobs in the publishing industry? Who’s responsible for diversifying the industry? How can authors and illustrators make the industry more responsive? What role does White Privilege play in the equation?

My responses:

I think all the questions are worth raising…again and again. Black Creators for Children (thanks to Tom Feelings and others) was started over 40 years ago as a self empowered group to encourage Blacks interested in the industry to prepare themselves for it. Nancy Larrick (The All White World of Children’s Publishing) and other educators and librarians kick-started efforts in 1965 to wake up the industry. The Council on Interracial Books for Children provided a tremendous boost in the 60s.

The Coretta Scott King Award was established 40 some years ago to recognize the stellar works of African American Book Creators for children. Yet, 17 years after that fact, my husband Wade and I self-published AFRO-BETS ABC book and later established Just Us Books because we couldn’t convince a commercial trade publisher in NY or Boston that this book was a

viable title for the industry to support. Remnants of the 1965 publishing model still exist despite the huge role that marketing and super book stores play in the publishing equation.

I was fortunate enough to have attended Radcliffe College’s Publishing Procedures Course in the summer of 1970. There were 2 other Blacks in the program that summer and neither found jobs in the industry immediately afterward. I landed a job as a trainee at an educational publishing house but trade house were definitely out of reach. Now, 40 years later it’s taken me and 6 other associates to come up with a list of 20 AA editors. And at least 8 of them are not working full time in the industry.

This is not to say that the industry has not changed or grown. There are obviously good, perceptive editors not of color who have recognized and championed the works of people of color. That is a good thing. People of color have demanded equity in school books for their children but the existence of “White Privilege” continues to have a tremendous influence and contributes in a real way to the way business is run and the way that the public at large perceives many books created by people of color.

The fact is that old habits die really hard. Book creators, and their editors tho’ must continually challenge assumptions about who POC write for, who needs African-American stories in school and trade books, why people buy books for their children and what kinds of stories those books tell.

Articles by Cheryl Willis Hudson

2 JulBook Talk with Abrams and ALA librarians 6/26/2010, Washington, DC.

My Friend Maya Loves to Dance

By Cheryl Willis Hudson

Copyright 2010 by Cheryl Willis Hudson. All rights reserved.

Good afternoon. My name is Cheryl Willis Hudson and I am delighted to be here with you today to talk about my book, My Friend Maya Loves to Dance. It is brilliantly illustrated by Eric Velasquez, edited by Howard Reeves, designed by Melissa Arnst and published by Abrams Books for Young Readers. Thank you for allowing me to share some of my thoughts and memories with you.

The publication of My Friend Maya Loves to Dance brings me almost full circle in my publishing career. It was forty years ago that I experienced and made my first attempts and experienced my first rejections by children’s book publishers. I submitted my first manuscript in 1970. My first poems for children were published in 1976. During that time there were only a handful of successfully published writers and illustrators of color. And my first real book was not published until 1987 some 17 years after the start. The state of publishing has changed quite a bit during this time.

Now in 2010, I hope that My Friend Maya Loves to Dance is a book that exemplifies and reflects the best of all that I’ve learned during these pass forty years.

My Friend Maya Loves to Dance is a story about an ordinary little girl who has an extraordinary friend. Dance—or specifically wanting to be a dancer, and loving everything about it, is the obvious theme of the book. After all, what little girl doesn’t dream of being a beautiful ballerina?

The narrator begins to tell the story:

My friend Maya loves to dance.

Wherever there is music

Maya takes a stance.

She points her toes,

Then away she goes.

Dancing is fun.

Maya knows!

The story is loosely based on a personal childhood experience. About 12 years ago on a visit to my hometown, I found a picture book in my mother’s house that I had completely forgotten about. But when I discovered it, I remembered that this book was a most treasured possession by my 8-year-old self. It was called A Child’s Book of Ballet. I loved that book! It was filled with pictures of little girls and boys studying dance and performing in a recital at the end. It reminded me that when I was a little girl I had dreams of being a dancer.

As an 8-9 year old, I took dance lessons with about 20 other little Negro girls at the Colored Y in Portsmouth, VA. A lady named Ms. Johnson was our teacher and someone else whose name I can’t recall also played a rickety old upright piano for us during our practice classes. The dance studio was a small space a in a worn out old building. The floors were cold and not so pleasant but we all dreamed of and lived for the annual spring recital where we could wear our tutus and beautiful costumes under soft and colorful theatrical lights. Alas, I loved to dance and had big dreams of being a ballerina, but I was not an especially graceful child. My dancing debut was one of a “rag doll” who didn’t have to be graceful at all. My mom had enrolled me in the class so I could learn to be graceful but needless to say, my dance career ended at about age ten not long after the spring recital. (smile)

(This photo was from a family Christmas card dated 1954.)

Nevertheless, the magic of the possibility stayed with me over my elementary and junior high school years and I fondly recalled those childhood dreams twenty-odd years later when I enrolled my own 5-year old daughter in similar Saturday morning classes at Maria Priadka’s School of Dance in New Jersey. Unlike my performance (held in the cafeteria-auditorium of Mt. Hermon Elementary School) Katura’s spring recital was on a big stage and looked almost like a professional Broadway production!

Part of my vision for My Friend Maya Loves to Dance was to be able to capture the magic of those innocent childhood dreams for hundreds of little black girls like myself who during the 1950s and 60s may have perhaps seen a photo of prima ballerina Maria Tallchief (who was Native American) but who had never seen an African American ballet dancer. Like the pictures in my favorite book, all the children, all the ballerinas were White.

Nevertheless, year after year, we still dreamed of joining the ranks of professional dancer and we sold tickets to the spring extravaganza and made our parents and our teachers proud of our perseverance, discipline, style and grace.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I want you to know something about the background of how I came to write this book. But also how it expanded into a story about friendship and a story about diversity and stretching boundaries. I started public school in the 1954, the year of the pivotal Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka Kansas. And I attended segregated schools for twelve years until the late 1960s when I graduated from an all-black high school. During that time, I would never have thought of writing a book like this. Nor could I have conceived of having or talking about a friendship like the one that Maya and Morgan share.

I must really thank illustrator Eric Velasquez for his thoughtful reinterpretation of my initial vision for this book. The paintings for this book are truly beautiful. Eric has made Maya’s story so real and so believable partly by using the talents of local children from a community dance studio as models for the paintings. Everything about Maya is full of the joy of “Dance”—all kinds of dance. Maya is totally absorbed in the music and the motion…Dance is a part of her entire being!

The narrator continues…

My friend Maya loves to tap

To jazz, blues and rap.

She dances in the hall…

In church and at the mall.

When she’s dancing

Maya has a ball!

As a children’s book creator, it’s marvelous to see my childhood “self” represented in this book—there are pages after pages of African American children who never were a part of the books I grew up with in the segregated south. There are boys and there are girls dancing together. And there’s lots of history infused into the images of this book—backdrops showing authentic musicians and lifestyles and African American culture, but very importantly, this is still a book centered around the experiences of a contemporary child—not only an African American child but any American child. I’m so happy to see that books spotlighting children of color are much more plentiful in 2010 than in 1956 or 1957 but there are still not enough to show the range of diversity in this country. But more than providing the gorgeous paintings of African American children, Eric Velazquez stretched the boundaries of the story by suggesting through his paintings that the narrator was somehow different from Maya.

Morgan, the unnamed narrator of the story, has a voice and a shared vision with Maya, her friend. It’s obvious that she has shared some experiences with Maya. Morgan says quite definitively that “dancing is magic for Maya and for me!” Morgan is an extraordinary friend. But who is she really? Who is this narrator? Why don’t we see her dance? If, she is sitting, as Morgan does in the last illustration of the book, how can the joy she expresses in her friend’s love of dance be so infectious? What is going through Morgan’s mind as she tells this story? How can she so generously share Maya’s story and how does Maya’s story relate to Morgan’s own experience? What is Morgan’s gift?

The answers are in the reading and re-reading of the words and the pictures of My Friend Maya Loves to Dance. It’s so important to me that a truly effective and successful picture book is not always a literal re-telling of word—that the visual imagery adds and reveals layers of sub-stories and allows for expansion of the imagination and the greater gifts that a child’s reading of the story can bring to it.

When I do book talks and readings, I’m always fascinated to see how children respond to the reading and the pictures and how they put their own spins on the stories that they hear. Initially, the audience of a recent reading at a bookstore in Montclair NJ did not have any African American children in it. The children were quite young and total absorbed in my reading. (Some had come directly from an earlier dance class with their parents and still had on their tutus.) Sometimes the children identify with Maya—other times the children identify with Morgan and her gifts. Sometime they notice Morgan’s differentness or disability and sometimes they do not. But ultimately they recognize the real theme of the book, friendship. That is something I’m so pleased to see that is so different from my experiences as a child over fifty some years ago.

As the narrator so aptly puts it:

My friend Maya loves to dream

Of recitals and soft lights

And performing for a queen.

Maya dances strong and free

With joy all can see.

Dancing is magic

For her and for me.

Author’s Notes, Cheryl Willis Hudson 5/25/08

My Friend Maya Loves to Dance

When I wrote My Friend Maya Loves to Dance, I was thinking about the thousands and thousands of little girls all over America between the ages of 5 and 12 who anxiously waited for Saturday morning dance classes at their local dance studios. In these dance studios, possibly located on the 2nd floor at the top of a flight of rickety stairs, was a room lined with full-length mirrors and horizontal barres. Inside, there was an upright, out-of-tune piano and outside of the main room single clothes hooks were positioned at child’s height along the walls on which to hang coats and wraps and outside street clothes and shoes. There was also a place to neatly position your dancer’s carrying case, the “official”, round hat-box shaped plastic container with the fancy writing and the line drawing of a graceful 9 year-old girl dressed in her leotards or tutu and soft ballet slippers. The glass case in the hall also held samples of dancer’s gear: leg warmers, black leotards, tights, pink ballet slippers, white Studio Tee-shirts and tiny porcelain figurines and trophies of male and female dancers.

The hard wood floors inside, more often than not, were not highly polished but instead scuffed from years of wear, limited budgets and the weight of hundreds of pairs of tapping feet that filled the room for tap classes after the ballet classes were over. The walls of the outside waiting room were lined with color photographs of little girls with hair pulled back tightly in little ponytails or buns, with just a hint of lipstick and make-up on their faces, smiling brightly in brightly colored costumes sewn from tulle, lace, and feathers for the pictures taken just before the annual spring dance extravaganza.

For a few little girls with obvious talent, the dance lessons went on for years and the star performers graduated to pointe classes where real ballet steps were skillfully and carefully taught. For others like myself, one or two years of modern dance or tap lessons was the limit and the spring extravaganza became the highlight of our childhood dreams to be bathed in the theatrical light of a professional dance career. Still, my favorite and treasured children’s book (I think the title was A Child’s Book of Ballet) contained picture of Anna Pavlova and Swan Lake along with correct postures of 1st ,2nd , 3rd , 4th, and 5th positions. The only decorative pictures placed on the wall of my bedroom were framed silhouettes of ballet dancers purchased from Woolworth’s Department Store.

Nevertheless, the magic of the possibility of becoming a dancer stayed with me over my elementary, and junior high school years and I fondly recalled those dreams twenty-odd years later when I enrolled my own 5 year-old daughter in similar Saturday morning classes in Maria P’s Dance Studio in New Jersey.

Part of my vision for My Friend Maya Loves to Dance was to be able to capture the magic of those innocent childhood dreams today for hundreds of little black girls like myself who during the 1950s and 60s never saw African American ballet dancers but who still dreamed of being in their ranks and who year after year sold tickets to the spring extravaganza and made their parents and teachers proud of their perseverance, discipline, style, and grace.

Wouldn’t it be nice today for all the young African American want-to-be ballerinas to see themselves in a book for young dancers? Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have those images in a book for another generation of dancers to cherish? Now there are professional dance classes offered by the Dance Theater of Harlem, and Alvin Ailey and Philadanco as well as many other regional dance companies and local dance studios for young people. I’m hopeful that children who attend those classes and their retro moms will appreciate the love and warm memories that went into the creation of this book.

Bright Eyes Brown Skin

13 JunCheryl Willis Hudson: Bright Eyes, Brown Skin

Talking Openly to Children About Racial Differences

Bright eyes, brown skin

A heart shaped face

A dimpled chin

Bright eyes, cheeks that glow

Chubby fingers, ticklish toes

A playful grin

A perfect nose

Very special hair and clothes

Bright eyes, ears to listen

Lips that kiss you

Teeth that glisten

Bright eyes, brown skin

Warm as toast

And all tucked in.

I wrote about one half of the words of that poem shortly after our son Stephan was born. He was a big baby—weighing in at 8 pounds 6 oz. And he was 21 inches long. He had a nice round head, freckles (that quickly faded after a few weeks) light brown skin and an infectious lopsided smile.

Stephan’s eyes were bright and hopeful and he jetted into the world. I immediately felt I knew who Stephan was and to the amazement of my obstetrician and the midwife on duty, I laughed heartily out loud on the delivery table when he took in his first breath. They washed him up, put him on my chest and I remember thinking, “He’s exactly what I expected, a beautiful black baby boy.” But I also said a silent, wordless prayer shortly afterward—a prayer I believe most African American mothers say knowing the challenges their male offspring face on their journey from birth to manhood.

I quickly put any negative thoughts aside and embraced our new son and the fullness of his possibilities for the future. I stoked his skin, I kissed and counted his fingers and his toes, I rubbed his bottom and brushed his still silky brown hair. I rubbed my nose on his nose. I smelled his baby fresh smell. My husband, daughter and I brought him with great joy.

Stephan’s birth was the inspiration for writing Bright Eyes, Brown Skin, (Just Us Books, 1991). Years later, I took the original words of my poem to my friend, Bernette Ford, a children’s book editor. Wouldn’t this make a great baby board book? I thought.

She agreed and with her expert editorial skills, Bernette helped to expand it into a picture book (very different from my original concept) that her husband George Ford illustrated with four children rather than one. The final result was a picture book about pre-schoolers that has become a great teaching tool for celebrating diversity. It is a book that deals openly with racial features—Negroid noses, full African-American lips, lush sculptural African American hair and varieties in dress and skin colors.

In Bright Eyes, Brown Skin facial features are presented naturally and positively. A nose is “perfect” for a face (not broad or derisively flat); hair is neither “good” or “bad” but simply a crown on a child’s head; skin is not dark—it’s a range of browns; eyes are not rolling or buck—they are bright and inquisitive. African American features that for so long have been presented and associated in stereotypical ways in children’s literature (akin to minstrel show imagery) are now being rendered directly and simply with no value judgment or racist baggage. The simple, straightforward text invites children of all complexions and ethnicities to take turns identifying their eyes, ears, noses, hair and clothes and to talk about similarities and differences among their friends.

There is a need for a broad range of books about African American children that are presented in a natural and accessible way.

Bright Eyes, Brown Skin presents all children with opportunities to talk about differences and similarities and familiar things because it places children in a natural, everyday pre-school setting. The associations are warm and positive and affirmative and Black children can see themselves realistically in the story line. For many African American children and also other brown children, Bright Eyes, Brown Skin affirms cultural identity. It helps children of color to see themselves as valued participants in the world and encourages them to talk openly about racial differences without feeling embarrassed, ashamed or marginalized.

Copyright (c) 2007 by Cheryl Willis Hudson, all rights reserved. Cheryl Willis Hudson is an author and publisher of children’s books who is also a member of the PEN America Children’s Book Committee.

Welcome to Cheryl Willis Hudson’s Blog!

4 JunYou’ve come to a place where you can find information about children’s books, diversity, parenting and family literacy.

As an African American woman, a working mother of two, a wife, an entrepreneur and an active member of my community, I’ve had to wear quite a few hats. But it has been my pleasure to say that most of these hats have had something to do with reading, creating and spreading good news about books. I love books!

I love books because they can enlighten us and inspire us and empower us and our children to make this a better world. Books can also simply bring us joy.

Books are definitely culture carriers. I believe all of us can learn more about each other and can make a positive difference in the lives of children and adults by sharing our unique stories and the wonderful diversity of people on this planet. Good books do make a difference. I hope you are visiting this site because you believe in the power of books and the value of the diversity they bring into our lives. I hope you will come back for new and updated features as our community of book lovers and creators continues to grow.

Warmly,

Cheryl Willis Hudson